Is Decentralised governance the democratic template of Web 3.0?

The ongoing pandemic has brought to light so many dysfunctional aspects of our social and political lives that many people are writing off their democratic ideals for good. What they ignore is that web technologies have been pioneering decentralised governance models for the past 10 years, with some astoundingly positive developments. Today, we present some big names that have fostered the survival of democratic values through Blockchain technology.

From consensus algorithms…

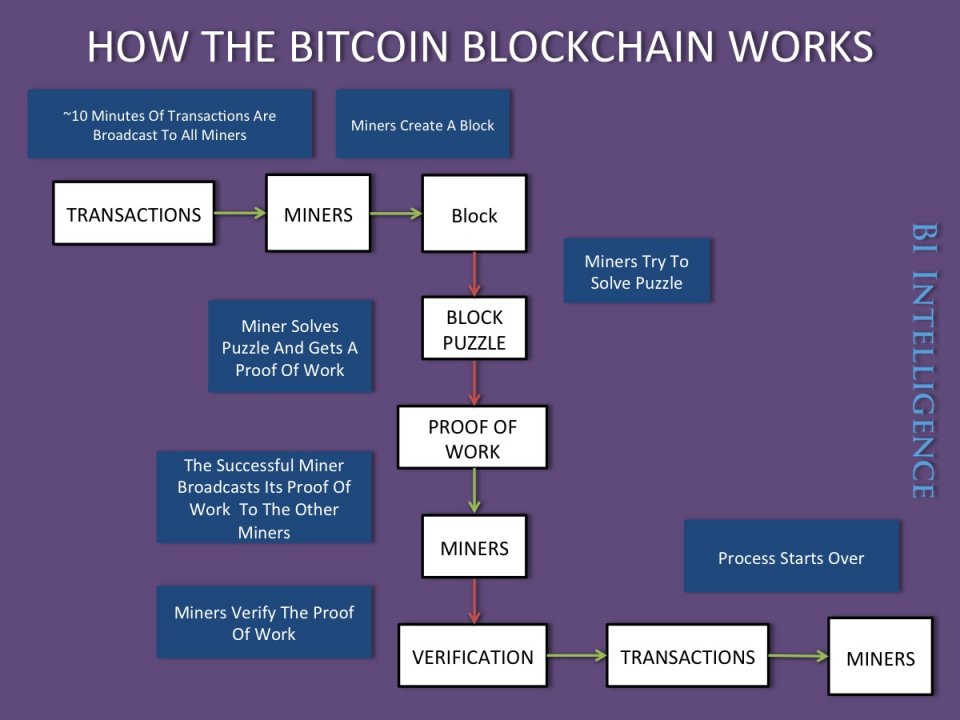

The first generation of blockchain technology revolved around the idea that through explicit, deliberate and concerted planning, it is possible to govern multiple entities (nodes) without requiring intervention from external actors a fortiori. In practice, this means that the originator(s) of the projects (i.e a group, a foundation or even an individual) decide(s) on what the underlying rules will be (i.e how often to issue a block, what the reward amounts to, how inflation is controlled, etc) and hard-code(s) these into the blockchain operations before the genesis.

There have been various implementations of this idea throughout the period 2010-2015, with the Bitcoin blockchain being the poster child of this approach, meanwhile numerous projects emulated its success. In fact, the mechanics of the Bitcoin blockchain are so seamlessly efficient that a lot of (uninformed) detractors have flagged the Bitcoin blockchain as being Artificial General Intelligence, if not “Alien technology”.

Yet, these protocols are still very much dependent on Human inputs and often subject to well-debated upgrades. Over time, it has become obvious that parameters that were originally set in the code can and should be reviewed to account for the growth of the network and the diversification of its participants. Changing the block size, redefining eligibility criteria for block rewards or forking on to a new blockchain are all legitimate attributes of governance on single-chain blockchains.

…to proposals…

It is only natural that the technology would evolve to meet the increasing demands of global users (i.e more privacy, more functionalities, better infrastructure, better user-friendly interfaces) in the post-Bitcoin boom era. Second generation blockchains focused on creating platforms that put the specific needs of the users at the center of their operations, opening the technology to a new cohort of users.

The end game of the Ethereum blockchain was always to decentralise computing technologies through smart contracts, so that every user can become a developer and create his/her own environment with its own set of rules and protocols. Within the short period panning 2016-2020, the model proposed by Ethereum has been hailed as a revolution equivalent to no-lesser than what Web 2.0 brought to internet users: autonomy, collaboration and organisation.

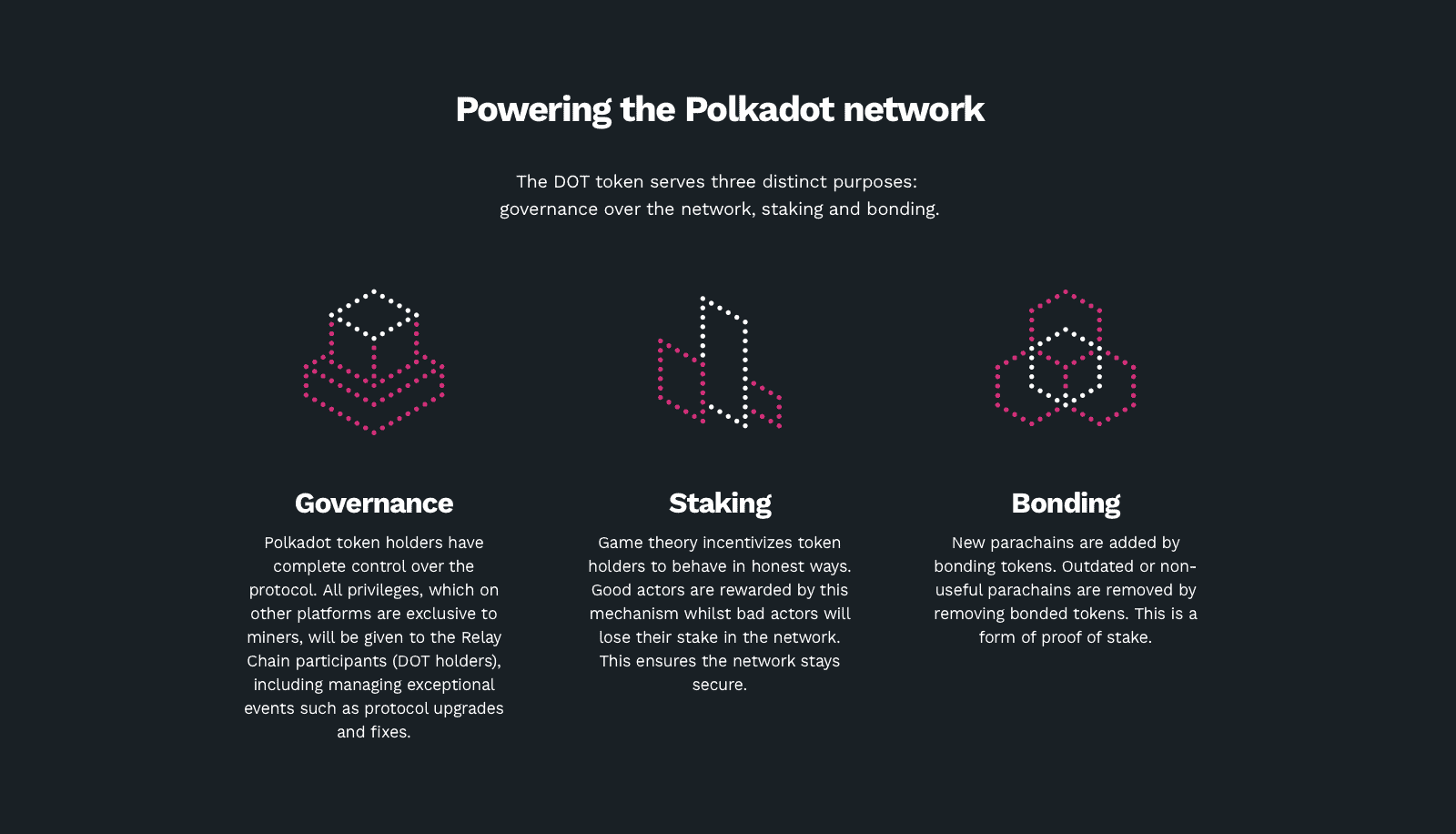

Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) are a form of governance that are thought to operate beyond any of our current institutional space and time. However, they still require the Ethereum Blockchain’s computational power to operate. In practice, any disagreement with an Ethereum Improvement Proposals (EIPs) or even high gas price (transaction fees) can force DAOs, alongside miners and developers, to move onto a different blockchain. Already, the Polkadot blockchain (that combines staking, on-chain governance and interoperability onto a modular multichain platform) is emerging ahead of Ethereum 2.0 which is scheduled for early 2021.

…and permissions.

As the existing blockchain technology struggled with coming to term with its rising popularity among the wider audience, established institutions and corporations took the opportunity to extend their reach. From inception, Blockchain technology had been conceptualised as a tool to open the field of network participation to as many people as possible. But this is only one of the many configurations available.

Since Big Tech and private companies entered the field, there has been a shift in the use of blockchain technology by private consortiums such as Libra and permissioned platforms like Corda. With permissioned blockchains, users need to be authenticated and authorised to become involved, and the management of these identification processes is not always part of regular blockchain operations.

As as an alternative to permissionless blockchains, the protocols have been developed to rely on a much more formal governance structure, very close to that of our “board of directors”. Proponents of censorship-resistant systems argue that there is no real advancement for governance in permissioned blockchains and that participants are always at risk on all fronts. Nevertheless, there is a degree of efficiency in decision-making and operations that is gained, which can be worth it for private corporations and national institutions.

As blockchain enters its third phase of development, there is a tremendous amount of anticipation as to what the future of governance will look like for users. What role will the miners/validators play? Who can effectively legislate on updates/upgrades? How can incentives increase participation/election rates? The technology certainly has a lot of challenges to clear in the short term.

Useful resources:

Eth hub: Governance on Ethereum

Deribit Insights: Polkadot re-denomination: a pratical look at on-chain governance

R3: How “Public permissioned blockchains” are not an oxymoron